Q&A with Mike Parr

Renowned Australian performance artist Mike Parr on the challenges of maintaining an independent practice since the 1970s, eschewing government funding and establishing one of Australia's landmark ARIs Inhibodress.

Renowned Australian performance artist Mike Parr on the challenges of maintaining an independent practice since the 1970s, eschewing government funding and establishing one of Australia's landmark ARIs Inhibodress.

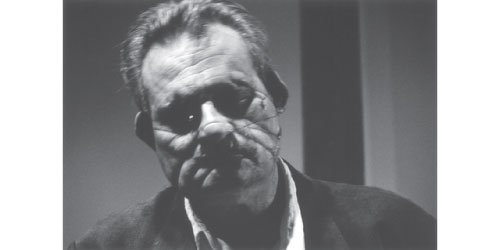

Image: MIKE PARR, UnAustralian (2003), photograph 100 x 180 cm. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sydney.

For a long while I couldn't. I've been doing performance art for 45 years since the 1970s and through the 70s it was regarded as non-art really. In recent years it's the other aspects of my practice that fund my performance art. I don't fund it by going to the Australia Council or seeking government support. It doesn't seem appropriate in the case of my kind of performance work, which is intended to be very confronting for the audience. I do a lot of drawing, printmaking, sculpture and other things. There's a strong relationship between all that other work and the performance work. I learn things from the performance work that can be applied to my work in other areas and it's the work in the other areas, the more traditional aspects of the visual arts that fund the performances.

In the 1970s, performance art wasn't really recognised as visual art. No one seemed to know what it was. I had to get used to the idea of sustaining a practice that was outside of the normal reception for visual art. So that gave me a sort of independence. I feel it's not appropriate to try and fund a really radical practice with government money. Because a lot of my work is very political, I want to be able to criticise aspects of a governments' policies and the culture as a whole. I want that independence. I think for a lot of younger artists at some point in their practice that critical tension with the culture has been lost a little bit. But I'm an older artist, I'm 70 so I've been around for a long while. I come from a background of attitudes that are a bit different to the current milieu. Having said all that it's important to say that I make art and I sell art through Anna Schwartz Gallery and I've been with the gallery for a long while. I don't renounce the art market and I have that sort of relationship.

I lived simply. I find drawing to be something that's very intimate and I can sort of devote myself to. My drawing and printmaking is something I do sell. I've relied really on my commercial gallery and I like that sort of relationship. I like that one-to-one relationship with private collectors. It takes a certain real commitment on the part of private collectors to support an artist down the years. They've got to believe in the work, pay for it and look after it, and you get to know some of these people and appreciate their passion for the work. I think that's a very simple relationship and it's the kind of traditional relationship that artists always look for. So it really works in my case. I find the idea of government funding to be very anonymous and you've got to fill out lots of forms. It's singularly obscure and inexplicable to me because a lot of the program is designed for social engineering objectives.

In those days it was very simple. Inhibodress was the name of the blouse factory - it was called Hibodress blouses and we just moved in. That was the first artist run space in Australia. There wasn't a context for that. I can remember that I sent out letters to a lot of people. Peter Kennedy and I had a series of meetings in 1970 and we invited a group of twelve artists who each contributed $30 a month, which seemed like an enormous amount of money at the time. We rented the space using the contribution. We began a running battle with Sydney Council at the time because we didn't put in a development application. We used to arrange to meet them but then never turn up to the meetings and kept this up for two years. The whole thing was very clandestine.

It was Peter Kennedy, Tim Johnson and I at the core of the venture. We knew what we wanted to do because at that time mail art and conceptual art were emerging. We had this enormous mailing list that was put together by David Mailer, in Britain. It was called the Eternal Network. It was like a prototype of the Internet now. We used mail because there were a lot of artist run spaces in Europe, North America and in Japan. We began inviting artists and putting together exhibitions at Inhibodress of international art. It's really interesting because I've got an archive and Peter Kennedy has several hundred artworks by artists who are regarded as some of the famous artists of the time. But back then, they were just like us. They sent in instructions for conceptual pieces and we began to do them at Inhibodress.

Inhibodress was entirely funded by membership. That was a crucial aspect of the cooperative. We also had a political end because of the Vietnam War. After 27 years of a conservative government, Australia was on the verge of electing it's first Labor government so it's important to bring that milieu into account. It was a very different time and Inhibodress was a kind of solution in that context. Australia and Sydney were very isolated. There was very little understanding of contemporary art. There was no other venue in Sydney doing performances and showing conceptual art. This was a complete novelty and so left of field, it created a lot of excitement. Strangely there was a lot of discussion in the press; Donald Brook in the Herald, Terry Smith writing for the Nation Review and James Gleeson writing for the tabloid papers. So you had critics that were prepared to debate these issues which happens online now. It's important to create that sort of discussion.

Mike Parr, The College of Cardinals (2005) Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sydney.