A Very Beautiful Laundromat

Using the laundromat as a small business model and place of public gatherings, Rebecca Conroy's latest artist led project attempts to strike the balance between the feast and famine of creative work.

Using the laundromat as a small business model and place of public gatherings, Rebecca Conroy's latest artist led project attempts to strike the balance between the feast and famine of creative work.

A few years back when contemplating the feast and famine economy of the artist-freelancer, I started thinking about the possibilities of an artist-led laundromat. The laundromat is a sound business model; it never goes out of fashion, you don't have to convince anyone to use it—and you can get a 24 hour licence to run it.

More than this, the idea of 'folding into' and symbiotically hosting an arts practice and arts space within a functioning artist-run business brings with it all the interesting complications and connotations that come with gendered labour, the rise of effective and intangible capital, and the entrepreneurial zeal that is rampant neoliberalism.

Founding and managing artist led spaces in Sydney over the past decade, I became irritated observing the peculiar rise of the business model for arts organisations. I would torture myself attending various business art seminars just so I could confirm the terrible and ill-fitting advice being dished out by economists and business people, some of whom brandished the credentials of working with such infamous finance cowboys as Enron and the Lehman Brothers. I thought this was bunk—and their snake oil was starting to burn. Struggling to survive in a political economy where our artistic process and practices are squeezed into square holes on a spreadsheet—things just never seemed to balance. And not just for artists: for an overwhelming majority of the planet's support systems and its climate, the 'business as usual' cancerous growth model, is literally killing us.

Earlier this year I took a job at a laundromat in the urban renewal precinct of inner South Sydney to become familiar with the operation, and to see if it really was in reality everything I had theoretically dreamt about. In theory, the laundromat will be run off 100 per cent artistic labour and would have a rostering system designed to handle the comings and goings of artists who needed a few shifts in-between gigs and residencies; it would pay $22 per hour which, when you crunch the figures, is an above average wage when you take into consideration much of the 'unkind' labour involved in artistic work. In addition, I became interested in how the physical uncomplicated labour of doing the laundry could provide some cognitive relief, and stand against the more messy and complicated and abstract labour of the artist. I also know for a fact that ironing can be practised as a kind of mindfulness whilst listening to a podcast by Eckart Tolle.

The 'care industries' which includes the outsourcing of domestic labour from the household, along with the needs of a growing elderly population and increased participation in the workforce by female parents has expanded the service sector in the Australian economy—it now takes up over 75 percent of employment, up from 50 percent in 1960. Neatly complimenting this is a rise in what is referred to as emotional or affective labour, in a growing 'experience economy' of lifestyle products, where the worker's personal interaction with the consumer constitutes much of the service—from the smile upon greeting, and the presentation of self, to the performance of intimacy to generate a unique experience.

At the same time labour across all sectors has become increasingly flexible, precarious and casualised. For the artist or creative worker, whose rising star also corresponds with the advent of the knowledge/creative industries, these conditions have merely placed the artist centre stage as the poster-child of neoliberalism. In addition, the place-based accumulation of capital through urban renewal strategies and 'creative cities' programs has further implicated the artist in the economic engine and discourse of the nation, as entrepreneur and driver of innovation, and subsequently dispersed the role of creativity beyond the elite confines of the 'art market'.

The most familiar and unfortunate model for public art is usually one that involves an object rudely imposed on council or state owned land. Typically it involves death by committee, and if it survives that, it is then shat upon from great heights by 'the public' who 'just can't handle it'. More recently, site based works that engage audiences temporarily, most of which are festival commissions to enliven urban precincts, have taken hold in cities across the globe, and are deeply implicated in the normalisation of gentrification processes.

I am interested in a third option: art-works manifesting as fluid encounters that self-righteously intrude in public spaces as private enterprise, without necessarily drawing attention to the artistic framework that sets it apart from that which it occupies/mimics. Using a combination of mimesis and trojan strategies, these art-works manifest by inserting themselves into the everyday economic operations of the city, essentially parasitising the cellular properties of the capitalist machinery.

I am referring to this as an imbricated practice, where the overlapping or thatching of practices knit together in a working solidarity to provide a function or purpose. And possibly where the pattern of overlay itself disguises the separate components resulting in the sum of its parts.

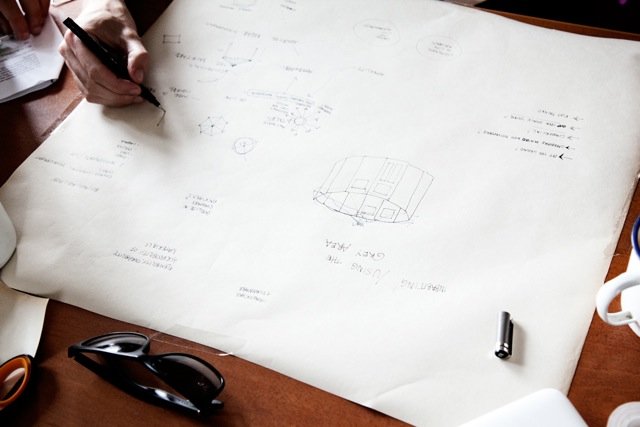

For me, the first iteration of this kind came out of a group art project I initiated in 2012 called Space Rangers. Our intentions were to mimic the strategies of the data survey to provoke some deliberately outrageous responses to city-making. I posed the idea of mining the city for data relating to land title and building use; a kind of military survey of the land before planning an invasion and occupation. The second experiment with imbricated practice was the site based intervention work Yurt Empire. Disguised as a rogue housing project, this 'art-work' intended to use the mimetic framework of installation art to install and playfully occupy an urban renewal site in the city of Sydney. Along the way we used the process of site brokering to open up conversation about affordable housing and land use permissions in the design and behaviour of cities.

Our aim was to smuggle 6 hand-made interpretative yurts onto an urban wasteland currently undergoing renewal in the City of Sydney, with the intention of living in them for three months as affordable housing. To gain access to sites, we would adapt the language of the project—switching from 'art' to 'place-making' to 'community engagement'. For these purposes we even made a promotional video for a fake company, that promised to "listen to the heart beat of the city" and "inject a unique and vibrant harmonic into the urban fabric".

To dissolve the work into the everyday where the audience or stakeholders are not entirely clear what parts are art and what parts are serious intervention, deliberately straddles a playful line between the deceitful and the provocative. But I am more interested in its purposefulness. How can art that is produced within the public sphere, occupy and provoke and actually transform the economy that produces the conditions of its existence? Is it possible for art to avoid capture by market forces, by remaining nimble, charming and just a little bit cheeky?

I would argue that stealth infiltration of the economy with art is the most productive and most 'useful' kind of public art. Not only does it provide an unusual encounter for an accidental audience, it can also be a useful income generating device for artists. If we have to be more businesslike, then it's time to do business our way. And maybe, the values shared by artists and cultural producers based on a desire to practice being more-than-human, might just correlate with the values of humans in general. And just maybe, doing the laundry might shift from the tedious and oppressive to the purposeful and sublime.

A Very Beautiful Laundromat is in development this year, starting with a series of dinner dates with economists in the UK, Canada and USA. The 100% artist-led laundromat intends to be operational in October 2016. More information here.

Rebecca Conroy is an interdisciplinary creature working across site, community engagement, and performative interventions through artist led activity. She has previously worked in the role of Festival Director (Gang Festival), Associate Director (Performance Space); Provocateur (Splendid Arts Lab & Artist Wants a Life) and has been the co-founder and co-director of two artist run spaces in Sydney, The Wedding Circle and Bill+George. From 2011 - 2014 she was conductor of The Yurt Empire, a rogue housing project and encounter in the inner city of Sydney. She has been widely published on topics ranging from artist led initiatives, site based practice, and contemporary performance. Currently Rebecca is researching and developing a project involving an international network of artist run libraries and alternative economics in the shape of a laundromat for 2016.