Infrastructural Activism

Art theorist and historian Professor Terry Smith on the role of the activist curator.

Art theorist and historian Professor Terry Smith on the role of the activist curator.

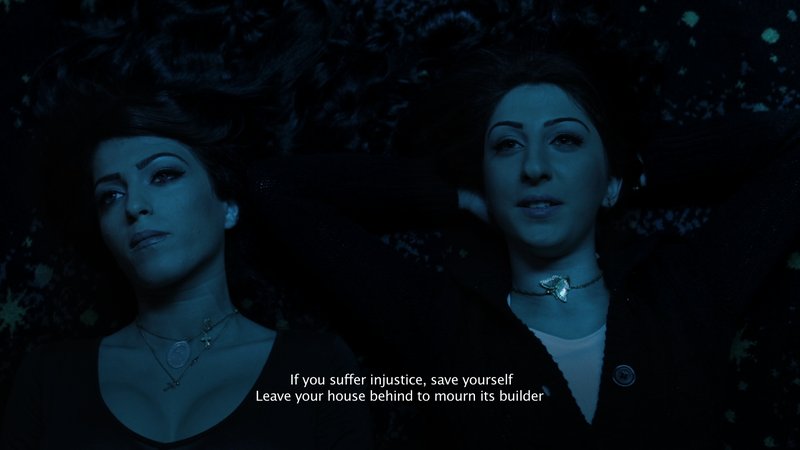

Image: Zanny Begg, 1001 Nights in Fairfield, 2015, 17mins single channel video. Courtesy the artist.

In recent years, curators have become increasingly active in presenting exhibitions of the artworks, banners, imagery, performances, actions, and events created by dissenting social movements, particularly those working to address climate change and against neoliberal globalisation. From Zanny Begg in Sydney to Nato Thompson in New York, this is happening all over the world. More power to it, as these issues become ever more urgent. But globalisation is also impacting the people, places, and relationships that enable art to become public, and doing so in deep but different ways everywhere. Activism to create, adapt, and sustain the artworld’s vital infrastructures is becoming an equally important task for contemporary curators.

During the past thirty or forty years, in many cities throughout the world, what we might call a ‘visual arts exhibitionary complex’ (VAEC) has come into being [1]. Today, we can see that in the world’s global cities, the VAEC is anchored by venues, such as metropolitan museums or state galleries, which claim to be “universal” repositories of the world’s art. They are surrounded by a host of mid-size and smaller public museums and galleries that have a more specialised focus on the art of places, periods, mediums, or even individual artists. All are collection-based, and operate as banks of concentrated cultural value. Commercial operations such as private galleries, auction houses, and art fairs, conduct a parallel circuitry, one that generates considerable contemporary energy, but is the opposite of historical in that it turns always on the point of sale. Yet the system as a whole depends for its creative and artistic vitality on quasi-institutional, alternative spaces of all kinds: kunsthallen, contemporary art spaces, artist-run initiatives––the enormous variety of constantly changing, sometimes temporary, but always experimental exhibitionary venues are where innovative art and curating happens first.

Artists, curators, art administrators, and activists everywhere want to work within a VAEC of a certain critical mass, one that has a dynamic of established versus emergent practices. They sense that such a setting is never sufficient to guarantee creative inspiration, but they know that it is a necessary pre-condition. Thus the commitment to infrastructural activism that is inspiring an entire generation, throughout the world, especially in places with only fragments of a VAEC.[2]

Let’s take two examples from Africa. Artist Meshac Gaba’s ongoing Museum of Contemporary African Art project. When invited to show in international art exhibitions, he creates mini-kunsthallen full of information about the provisional, chancy, and volatile conditions in which art is made throughout Africa. His installations are ghosts of an absent infrastructure for experimental art. Similarly, The Center for Historical Re-Enactments, established 2010 in Johannesburg by a group of curators, artists, and writers led by Gabi Ngcobo, encourages site-specific artworks that “investigate and create dialogues between artistic practices in order to reveal how within their constellation certain histories are formed or formulated, repeated, universalised and preserved.” (see http://centerforhistoricalreenactments.blogspot.com.) The initially promising yet stillborn experience of the Johannesburg Biennial has been a topic. Infrastructural activism not only builds the basic platforms for art to become public, it also operates as an important enabler of broader cultural change.

No surprise, then, that in these places, and in well-provisioned cultures, the most effective infrastructuralists are under attack from conservative politicians and governments. In Europe and Australia, the Neoliberal Pacman has recently arrived at the level of local government, with deleterious consequences for the not-for-profit sector, specifically independent art spaces. Mid-scale and alternative exhibitionary venues have been obliged to divert even more of their energies into grant-seeking and reporting to increasingly unresponsive patrons who seem intent on throwing them into the open market, thus compromising their role of incubators of innovation for the entire system. Artists’ representative organisations, such the NAVA, are being deliberately defunded. The irony is that all this is occurring at a time when globalising capital is failing as a system, and is being widely rejected by those it has mislead and exploited.

Arts infrastructure-builders are envisioning different forms of community; those that will flourish after globalisation implodes. Strategies of survival are the order of the day. There are no simple, universal answers. Connecting through lateral or regional networking is one way forward. Since 2004 ‘tranzit’ has been coordinating the activities of independent artists’ initiatives in Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia, as well as showcasing its network model at venues elsewhere. In Ho Chi Minh City, Zoe Butt leverages international interest in Sàn Art’s exceptionality as a platform for contemporary art. Residencies for artists, curators, writers, and administrators have become a key medium for such networking: between, for example, Platform Garanti in Istanbul, Ashkal Alwan in Beirut, and the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo, despite the last’s recent closure by Egyptian authorities. Infrastructural activists are like chameleons: when your organiation comes under attack, change colour, shift shape, and start up again, differently, nearby, and across longer distances. These days, connectivity is a big part of making a place for art.Professor Terry Smith is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh, and author of Talking Contemporary Curating (New York: Independent Curators International, 2015).

[1] I borrow the concept from Tony Bennett, a sociologist at the University of Western Sydney. His pioneering books, such as The Birth of the Museum (1995), track the history of museums, worlds’ fairs, and publicity in various forms, from the eighteenth century to the present, mainly in Europe and the United States.

[2] In our conversation in Talking Contemporary Curating (New York: Independent Curator’s International, 2015), Okwui Enwezor listed such individuals in just one region, the Middle East:

Lamia Joreige is an artist, but she’s also the co-founder of Beirut Art Center. Also in Beirut, there is the Arab Image Foundation, whose work has been supported and undertaken by many artists, including Walid Raad, Akram Zaatari, Lara Baladi, and Yto Barrada. Christine Tohme, a curator, is the founder of Ashkal Alwan and its platform Home Works. Tarek Abou El Fetouh founded the Young Arab Theatre Fund in order to facilitate a range of projects. In Cairo, a group of young women created CIC, the Contemporary Image Collective; they are artists, but also use this collective to build civic bridges. In Tangiers, Yto Barrada and Bouchra Khalili created the Cinémathèque de Tangier. In Ramallah, the Riwaq Biennale is led by artist Khaled Hourani. In Lagos, there’s Bisi Silva at the Centre for Contemporary Art; in Dakar, Koyo Kouoh at Raw Material Company; in Rabat, Abdellah Karroum at L’appartement 22, and so on. It’s an amazing proliferation . . .(page 102)