Strengthening the status of the artist

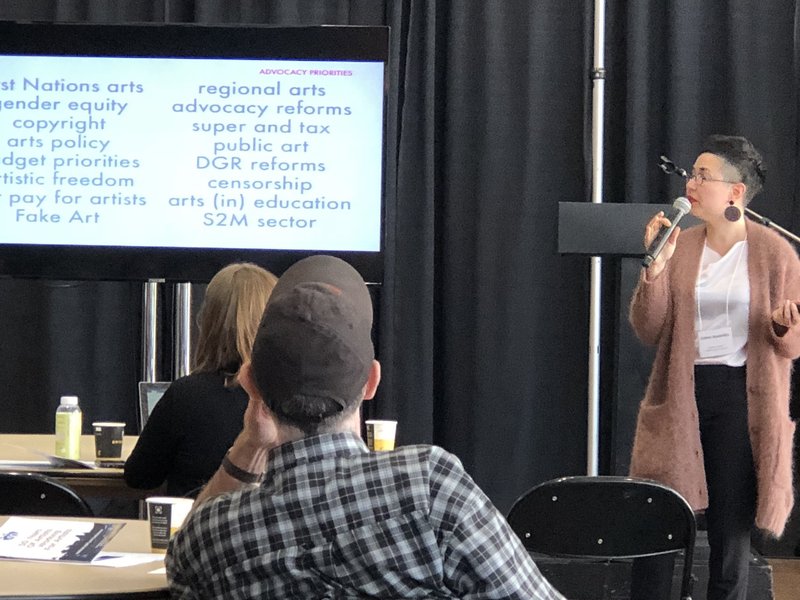

Image by Zandi Dandizette for CARFAC National.

Image by Zandi Dandizette for CARFAC National.

How do we recognise, understand and value the status of the artist? In our public life and public discussion, our education institutions and curricula, our workforce, our taxation and social security systems, our economy old and new, and in our culture?

In Canada there’s an Act for that: it’s called Status of the Artist, and it’s made ground-breaking agreements possible that set nationally enforceable standards for artists’ rights, contracts and fees.

It’s also had an impact on that more everyday understanding of artists having a unique status – one that helps ground debate on the nature of artistic and curatorial practice, as well as on the ethics of what constitutes collective negotiation, pressure tactics, and good and bad faith bargaining.

On 7-9 September 2018 I was part of CARFAC 50 in Ottawa. CARFAC is Canadian Artists’ Representation / Le Front des artistes canadiens, NAVA’s counterpart organisation in Canada. The two have long enjoyed a collaborative relationship, with CARFAC licensing and adapting the NAVA Code of Practice for its Best Practices a decade ago. At the conference, advocates from all over Canada came together to reflect on fifty years of achievement for artists and find collective ways forward. I presented on NAVA’s work in the current Australian political context – refreshed with yet another prime minister and a newly returned arts minister – and had some invigorating and important discussions that were incredibly useful for our working context.

Status of the Artist is a UNESCO Recommendation that was made in 1980 and has since been adopted by many countries – initially: Chile, Czechoslovakia, Finland, France, West Germany, Honduras, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Madagascar, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, San Marino, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Ukraine, UK, Zambia, and Canada. Each of these countries reported on their implementation of the Recommendation within the first three years, with varying degrees of progress made. In France, for example, there’d long been social security, tax and intellectual property measures that support artists, and in Ireland, artists also enjoyed many workplace and unemployment protections.

When articulated into legislation, Status of the Artist embeds the unique characteristics of artistic practice into policy and law on public recognition, education, health, welfare, social security, cultural rights, working conditions and labour movements. It can also provide the framework through which sector bodies can achieve certification to bargain collectively on behalf of their members on working conditions and fees. In Canada, those organisations certified for the visual arts are CARFAC and RAAV, Le Regroupement des artistes en arts visuels du Quebec.

In Canada, a historic Scale Agreement was reached in 2014 between CARFAC and RAAV, and the National Gallery of Canada, and it was renewed earlier this year. Unfortunately, to get to that agreement, CARFAC and RAAV were obliged to take their negotiations all the way to the Supreme Court by evoking the Status of the Artists Act’s provisions on bad faith negotiations, after the Gallery abruptly changed its lawyer and its strategy at the cusp of reaching an agreement some years earlier. There was barely a dry eye in the house as David Yazbeck, a long-time CARFAC member and board member, and a human rights and labour relations lawyer, told the story of those negotiations, for which he had worked many pro bono years to represent CARFAC Members. It had taken more than a decade to achieve that win, to which galleries across Canada turn as the standard for artists’ fees and contracting conditions.

So how effective has Status of the Artist been? Professional opinion in Canada is divided. Because Canada lacks our system of federalism, key legislative frameworks such as labour laws vary from province to province, making it impossible for national negotiations to bind galleries across Canada. The various CARFAC offices across the country are therefore separate entities affiliated with CARFAC National, while RAAV is a partner, and the various negotiating frameworks vary from province to province. The relevant act in Saskatchewan, where all the national work began, is not a Status of the Artist but rather the Saskatchewan Arts Professions Act, which mandates written contracts for engaging artists, but does not mandate their terms nor minimal conditions.

Resale royalty – or more specifically, lack thereof – is a hot topic in Canada, and is a priority for CARFAC. The example most often cited is the story of Inuit artist, Kenojuak Ashevak, who sold her piece Enchanted Owl in 1960 for $24. It was later resold at auction for $58,650, and yet the artist received nothing. Today, in recognition of Ashevak’s national acclaim, a print of Enchanted Owl is also in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada. Status of the Artist also recognises what’s unique about artists’ intellectual property rights, and should offer a strong foundation to those negotiations – hopefully, not as drawn out as the Scale Agreement!

There’s also the question of who is an artist and therefore who is supported and protected by the Act. One of the most compelling discussions at CARFAC 50 was led by Clayton Windatt, a Métis non–binary multi-artist and Executive Director of ACC-CCA, the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective / Collectif des commissaires autochtones. The role of the independent curator cannot be underestimated, argued Windatt. While institutional curators tend to work with existing work, independent curators tend to commission new work. They often have deep culturally specific knowledge as well as broad skills in research and facilitation, as well as fabrication and installation. In Australia, independent curators are not eligible to apply for many artist grants, and few specific funding opportunities exist – The Freedman Foundation International Scholarship for Curators administered by NAVA, for example. Windatt is at the early stages of developing a curatorial fee schedule, which is going to be of great interest to us at NAVA as we make similar investigations.

The question of who is an artist also relevant for many of other the rights and opportunities accorded by Status of the Artist. The recent trial of Guaranteed Annual Income in Ottawa, ending just as our conference began, was Canada’s first foray into a universal basic income system. Much as it clashes with the ideology of neoliberal governments who reject social security as a public value, this approach demonstrates that it’s actually cheaper and less of a burden on the state to guarantee a basic living wage than to administer a range of welfare benefits. The outcome of trial is yet to be analysed and reported, and the Canada Council will be looking at the impacts on the artists who were involved in the scheme.

So what’s next for Status of the Artist around the world? UNESCO has recently launched a Global Survey on Status of the Artist, with findings to be presented at the General Conference in late 2019. In launching the survey, UNESCO notes the urgency at this “critical time when artists and creators around the world have reiterated calls for stronger rights, fairer remuneration, copyright reform, legislation to give creators a fair deal from global companies, especially those proving a platform for user-generated content... [while] artists’ employment and social status continues to be precarious, with low access to social security, pensions and other welfare provisions.” My trip to Canada was made possible by the IGNITE Fund of the Copyright Agency who, as of late last year, incorporates Viscopy and exists just as much for visual artists as writers. Their management of rights and licensing for members ensures an income for thousands of artists, and their Free Is Not Fair campaign has been enormously impactful in highlighting precisely what UNESCO warns. During CARFAC 50 the European Parliament voted in support of the rights of artists and journalists whose work is commonly used as the “content” that earns incomes for tech giants, who must now pay for the work that they publish.

“Much awaited by artists and cultural professionals,” UNESCO continue, “the survey’s findings should serve to inform policy decision makers and send an empowering message to the global community – one that allows future generations of creators to make a living from their work.” NAVA will be watching carefully as we investigate the potential for Status of the Artist in Australia, as one of many possible mechanisms for the national application of the Code of Practice.