Change the Conversation From Surviving to Thriving

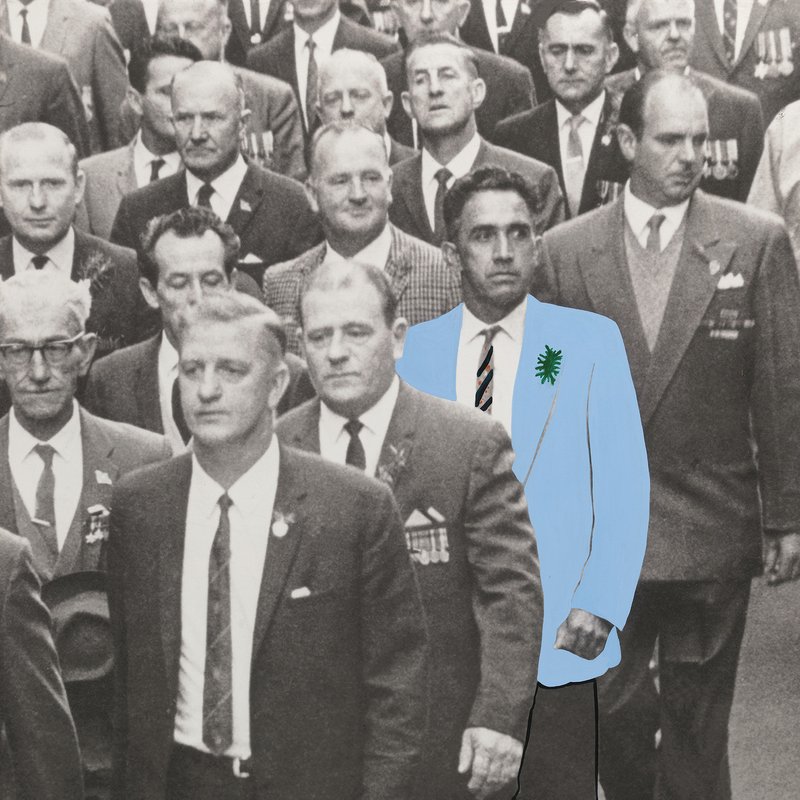

Bronwyn Bancroft, Time marches on, 2010 (cropped), mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and the Australian War Memorial.

Bronwyn Bancroft, Time marches on, 2010 (cropped), mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and the Australian War Memorial.

The words “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’, ‘Blak’, ‘Indigenous’, ‘First Nations’ and ‘First Peoples’, are used interchangeably in this article to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, and global First Nations artists in the Australian arts and culture sector. NAVA understands the complexities in the use of these words and that some First Nations peoples may not be comfortable with some of these words. We would like to make known that only the deepest respect is intended in the use of these terms.

It is no surprise that there is currently a lack of agency and deeper representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in our arts and cultural institutions in Australia. It is made clear in comparing the existing governance structures and employment figures across the Australian arts sector, whether in small to medium organisations, or in our major public art museums and galleries. While there have been some advances in recent years, the reality of a European dominated cultural sector in Australia and across the world makes a clear case for more active strategies and policies around cultural safety and re-Indigenising spaces for us to continue growing as the oldest continuing arts and culture makers on this earth.

First Nations artists and arts workers often talk about the great satisfaction we get from working with our people and our stories. Furthermore, there are often conversations around how important it is to provide cultural contexts and information to other, non-Indigenous artists and arts workers and how this also contributes to meaning in our work and giving back to community. There has been an increasing swell of interest in First Nations art in Australia and across the world, which some may think would have eased some of the burdens faced by those who have spent decades systematically excluded from major museums and galleries.

In numerous conversations in the lead up to this piece, First Nations peers have stated and agreed that while the industry’s gatekeepers are now paying some attention to our cultures, establishing genuine relationships with them is still disproportionately harder for First Nations artists and artists of colour than it is for our white peers. Often when we are heard, it is through our own self-advocacy in a system designed against understanding blakness. The understanding of lived experiences of First Nations cultures is very little, and when putting it into context, the nuances of many of the issues of our artists and curators is that these nuances get lost in audiences that have pre-conceived understandings about what it means to be First Nations. The challenges begin early with the pressures of ensuring that the work is presented, articulated, and contextualised in very specific ways compared to non-Indigenous artists. A common thread in conversations have consistently described accounts of racism in the sector. More specifically on a systemic level, non-Indigenous policies and practices have often failed to align with Indigenous worldviews, and as a result become counterproductive to equality in the sector.

These challenges lead to feelings of responsibility to enter as many spaces as possible, which can lead to problematic arrangements and burnout for many First Nations peoples. The cost of our First Nations artists and arts workers not caring for ourselves and practicing self-care can lead to the burnout and loss of practitioners across the sector. Artists have often described a sort of ‘invisible labour’ we take on to survive in an art world that is not build to accommodate First Nations artists. The stress of being a First Nations artist and/or arts worker today, that is unique to First Nations practitioners include:

The challenges are enormous, but for change to happen we need everyone, Indigenous and non-Indigenous to be on board. It is important to remember that we, as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander practitioners, are best placed to lead this change.

In conversations and workshops, most recently SHARE. EAT. CONNECT. hosted by Campbelltown Arts Centre as part of the current exhibition Ok Democracy, We Need to Talk, with practicing First Nations artists, we have identified some recommendations to ensure that the contribution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and global First Nations peoples working in the Australian arts sector is being genuinely valued:

This is not to say that change isn’t occurring. There has been a huge shift in curatorial practice within arts and cultural institutions in the last 20 years, and we can see it changing more and more with each generation. But there is still a long way to go to create a stronger understanding around agency, deeper representation, care and safety for First Nations artists and arts practitioners. Let’s change the conversation from surviving to thriving.

This article is supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW.