Key levers in arts policy: the vexed question of operational funding

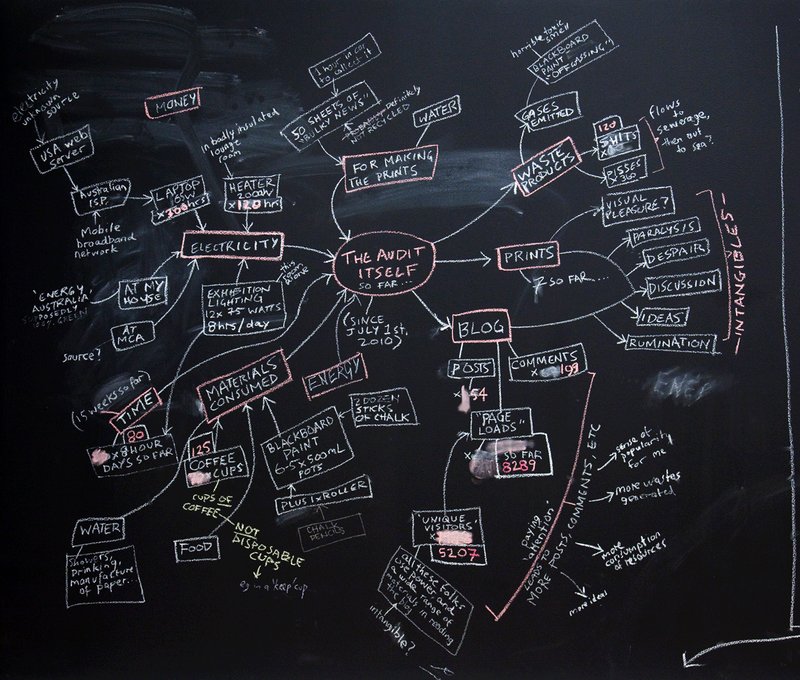

Lucas Ihlein, "The Audit Itself (so far)", created as part of "Environmental Audit", MCA, 2010. Chalk drawing.

Lucas Ihlein, "The Audit Itself (so far)", created as part of "Environmental Audit", MCA, 2010. Chalk drawing.

With the Australia Council’s Four Year Funding for Organisations announcement due on 30-31 March, the nation’s publicly-funded arts sector is bracing for impact. Expectation management has been clear: the sector should expect a lower success rate with fewer organisations funded, and given the 2016 outcome, the impacts will have far-reaching consequences given the complex interconnectedness of the arts ecology.

However, the Australia Council’s investments cast just one set of strengthening tendrils across that ecology. Local, state and federal governments, as well as philanthropy, each play a vital role. But why are those investments important? How is public investment in core operations vital to a thriving arts industry? Let’s take a deeper look.

What is operational funding for organisations?

Operational funding programs are competitive grants that support those core business costs that can’t be funded in other ways – basics like administrative staff, rent and office expenses, marketing and audience development. While project funding allows organisations to create and present work and pay artists fairly, that kind of funding doesn’t support core operations – administrative costs are explicitly excluded.

More and more, project funds also have high expectations of applicants in demonstrating other sources of funding or self-generated income for those projects. To leverage that – to be in the best position to secure government or philanthropic project funding, and to boost their other sources of income – organisations need to be able to rely upon a solid core of operational sustainability. And yet it’s precisely that solid core that’s being undermined by the current trends in operational funding.

The role of the Australia Council

Recognising the value that organisations are able to leverage when their core is secured, the Australia Council’s 2014-2019 Strategic Plan A Culturally Ambitious Nation also recognised the value that that brings to all Australians. In the plan, a new Six Year Funding for Organisations program was announced, and companies across Australia devoted many thousands of hours to applying.

While the Major Performing Arts Framework had provided secure, non-competitive, long-term funding to a few dozen large companies for decades, as well as security of employment for hundreds of musicians and artsworkers, for the first time the Australia Council was investing ambitiously in small-to-medium companies, strengthening their vital role in driving artform evolution, artists’ careers, audience development, sector capacity and industry development.

But despite personally launching the plan in 2014, just months later the then Minister for the Arts unexpectedly destabilised the Australia Council by withdrawing the funds that strengthen its own core. The Australia Council was forced to cancel a range of high-demand programs including Six Year Funding, undermining its strategic objective to invest meaningfully in the organisations who sustain the arts across the nation. The revised, diminished Four Year Funding program offered less money for fewer organisations, and now, four years later, fewer organisations than that.

As the Australian Government’s arts funding and advisory body, the Australia Council is the only source of public funding for organisations of national scope. It also learns a great deal from the organisations it funds, reapplying that knowledge into its sector development work. A diminished organisational investment program therefore diminishes the Australia Council’s own capacities to work strategically for the entire sector. This is not just about funded organisations; it impacts on the entire ecology.

The retreat from operational funding: other government and philanthropic approaches

Meanwhile, operational funding prospects all across Australia are either decreasing or vanishing altogether. While multi-year organisational funding used to be annually indexed, assisting organisations to meet annually-rising costs of doing business such as wages and rent, most states and territories no longer factor in annual CPI increases. Worse, when the time comes for organisations to reapply, they’re offered the same amount they were offered before, regardless of what they applied for. Regardless, that is, of the increasing demand or the changed industry conditions that they’ve clearly demonstrated in their funding applications, as well as their obligations to support industry standards including fair pay for artists and artsworkers.

What does this mean for governments, for taxpayers, and for the arts? A public investment in the strengthening of creative industries has actually become an investment in their contraction.

In Victoria, where a Creative Industries Strategy has been in place for a few years and is currently under review, organisational grant indexation ended a decade ago. In South Australia, there are organisations in the precarious position of receiving the same amount unindexed for not ten but twenty years.

While the Major Performing Arts Framework was recently revised, an opportunity was missed to incorporate the Visual Arts & Crafts Strategy and create a comprehensive, multi-artform program of long-term investment. Instead, in the current round of VACS renewal, some currently-funded organisations have been offered much less than what’s required to sustain their work.

For the contemporary arts more broadly – that expanded field beyond visual arts and across experimental, ephemeral and public space practice – the Australia Council is a minor element. Even for its core disciplines in the visual arts. The majority of Australia’s galleries – in particular, regional and suburban galleries owned and operated by local government – are ineligible to apply to the Australia Council. However, they too fall afoul of the retreat of core funding. Increasingly, regional councils are merging the operations of their galleries and performing arts venues and appointing a single venue manager rather than gallery directors and theatre specialists. This drastically undermines local capacity to foster what’s unique about regional culture, supporting artists to sustain careers locally, as well as nurturing local arts audiences.

What is the role of philanthropy in supporting the core operations of arts companies? While philanthropists are passionate about investing in artists’ and organisations’ capacities to make great work, they do not have a role in assessing national industry needs and addressing those through specific policy and funding programs. After the 2015 attacks on the Australia Council, leading philanthropists Neil Balnaves AO and Luca Belgiorno-Nettis championed the role of the Australia Council, making it clear that philanthropy cannot be relied upon to fill a policy vacuum.

A decade ago the Myer Foundation stopped offering a range of funding programs for organisations, focusing instead on the impactful Sidney Myer Creative Fellowships for individuals, which were launched in 2011. More recently they’ve come full circle, renewing a priority focus on multi-year, unrestricted, operational support. At least three other major philanthropic trusts are seeking high-level industry advice right now on the best possible role they can play when it comes to investing in the operations of companies for the sustainability of the sector.

Organisational investment as a policy lever

A key reason for public investment in organisations is that it allows governments to achieve a diverse range of policy goals by embedding expectations into funding agreements. These expectations include not just measures such as numbers of artists supported, works shown, audiences attending etc., but also, strategies such as First Nations priority, diversity, accessibility, regional focus, industry collaboration, fair payment for artists etc. Devolved funding, where governments fund organisations to implement grants programs for artists, is also a critical lever, ensuring that artists are supported by artsworkers who are often better placed than public servants to understand their specific needs.

A particularly effective set of levers for this kind of partnership with government is its relationship with sector service organisations. These industry peak bodies such as NAVA work closely with artists to sustain their practice, with organisations to strengthen their capacities, and with the entire sector to champion best practice. Service organisations are Australia’s nationally-focused experts in their artform field. They are also some of the organisations hit hardest by the retreat in core funding, with companies such as Playwriting Australia and Ausdance National teetering at the brink of closure and more recently finding ways to reorient their work.

Create NSW, one of the only state government bodies to have offered a specific funding program for service organisations, is currently reviewing that program through this survey (note the browser problem that hides the “Strongly disagree” function from some of the multiple-choice questions). In Victoria, where there is no separate funding category, service organisations were instrumental in restoring indexation to organisational funding back in 2007, when the then Arts Victoria commissioned Deloitte to undertake a S2M study into the scale and scope of the sector and the impacts of government investment. Sadly, the value of that work has not been preserved, and organisations whose core funding isn't indexed have been cutting back on programs and services for years.

Questions to ask

Governments can’t create artworks and nor can they inspire audiences. They can, however, create the conditions in which our culture thrives.

At this complex time, further research and investigation is needed to understand the relationship between public investment in sustainable arts organisations and a thriving Australian culture.

Questions for researchers:

Questions for policy-makers:

Questions for journalists: