Structural transformation to support gender equity in the arts

Institutions must take on a proactive role to address challenges around how women and gender diverse people are represented and how their work is presented, collected and valued.

Institutions must take on a proactive role to address challenges around how women and gender diverse people are represented and how their work is presented, collected and valued.

Manifestations of gender inequity and bias in the visual arts play out in complex ways. These are specific to the sector yet are informed by prevailing social attitudes, biases, and prejudices that have shaped gender inequality in society. A proactive role by institutions is needed to address structural challenges around how women and gender diverse people are represented and how their work is presented, collected and valued.

The new Gender Equity section in NAVA’s Code of Practice for Visual Arts, Craft and Design (the Code) provides ethical approaches for institutions and individuals to support opportunities and representation for women, trans, non-binary and gender diverse artists and address gender disparity in fees. Written by Miranda Samuels, educator, researcher and co-editor of the forthcoming 2024 Countess Report, this section challenges organisations to interrogate the gender power relations that form Australia’s systems and structures.

Gender diversity beyond a strict gender binary is a well-understood and deeply rooted idea in many cultural contexts, notably in First Nations communities. The settler-colonial project of gender brought denial and erasure of genders and kinship structures outside of the binary. It continues to be forcefully applied to frame ongoing relationships with First Nations peoples and reduce their existence and agency. There is much to be done to ensure the sector is accessible to artists and arts workers who are not cisgender and may identify as trans/transgender, genderqueer, non-binary, brotherboys, sistergirls and other experiences of gender identification. Reinstating kinship and truth in representation fundamentally supports First Nations’ agency and challenges colonial reductions of gender.

In the Western tradition of art, women and gender diverse artists have historically been excluded from participating in the professional domain of art and art education. The 2019 Countess Report, a four-yearly data snapshot of gender representation in the contemporary visual arts compiled by art activist collective Countess.Report, revealed significant gender equity gains across some sector areas. The percentage of women artists in commercial galleries increased from just over 30% in 2014 to over 50% in 2018.

Yet, in other areas, gender representation remains low. Over 70% of art school graduates entering the sector were women, compared to just 12.5% of state gallery directors. Women arts workers have historically been well represented in arts administration positions but continue to be significantly underrepresented in such leadership positions across the cultural sector.

Likewise, the gender pay gap is wider in the arts than the average gap across all industries in Australia, according to 2017 data from a major economic study of professional artists in Australia. As well as broader social prejudices, stereotypes and biases, artist mothers and parents face barriers to employment and participation including insufficient material support, such as childcare and parental leave for casual and part-time arts workers. Additionally, limited professional development opportunities for parents, such as residencies that accommodate families and age limitations on awards and residencies, might exclude artists who have taken career breaks to care for children. These factors can make a sustained artist's practice challenging while bearing and raising children.

While gendered harassment can occur in any setting, the Code recognises that ‘areas of the arts sector which operate in a relatively informal and unregulated manner can make such instances more prone to occurring.’ The variation in work environments across the industry can increase the chances of misinterpreting acceptable behaviour at work. Additionally, events like exhibition openings, where alcohol is served, can blur the boundaries between work and socialising.

Organisations are responsible for identifying and addressing how power, access, and privilege operate across practices, systems, and structures in the organisation and the wider industry. A practical place to start is developing and implementing gender-equity policies that outline measures, policies, and targets to promote gender equity. Policies may include gender affirmation leave, editorial standards for gender-inclusive language, childcare policy and support available, and more.

The Code recommends that women, trans, non-binary and gender diverse people should form a significant part of an organisation's governance. It is essential that those in decision-making positions, such as board members, directors, CEOs and executive staff, are reflective of the broader arts community.

Establishing strong workplace culture, equal opportunity policies, and inclusive practices will help contribute to welcoming, safe, respectful and open environments in the workplace. More equitable governance can be implemented through various ways, such as professional development opportunities, insurance of equal pay, non-biased hiring practices (see Equitable Application Processes), mentorship programs, and up-to-date knowledge of relevant federal and state legislation. Other recommended processes in the Code include promoting pay transparency and providing all-gender facilities, access to childcare options outside of regular working hours, suitable spaces for breastfeeding and flexible hours to employees.

Key to tracking your progress on gender equity and being accountable to your equity goals are evaluation and monitoring systems. Self-report data on gender representation and pay gap analyses should be ethically collected and conducted at regular intervals regarding both employees and gender representation in exhibition programming.

Institutions should not settle for merely including marginalised voices in the established body of work. Instead, they must think carefully about how creative labour, practice and outputs are valued economically, socially, and culturally. The Code’s recommended processes promote concrete steps and inclusion strategies to redefine gender power relations in the arts.

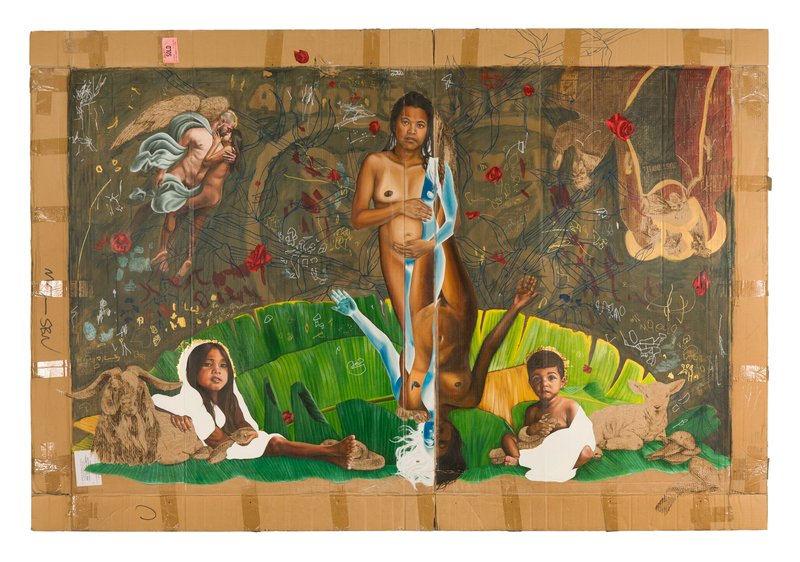

Image: Marikit Santiago, Original Sin (2018) acrylic, oil, pyrography, pen, 9ct gold leaf, (pen and paint markings by Maella Santiago and Santi Mateo Santiago) on found cardboard, 148cm x 218cm. Courtesy of the artist and The Something Machine, Bellport NY. Photography by Garry Trinh.

ID: Photo of a painting on found cardboard that portrays Santiago depicting herself, pregnant and nude, with one child in utero and two more by her side. In the background are banana leaves, farm animals, and various pen and paint markings by the artist’s children.