Gendered decision making?

Esther Anatolitis on the accountability of decision makers at Australia's major art institutions.

Esther Anatolitis on the accountability of decision makers at Australia's major art institutions.

(Please note this article contains strong language)

“State Museums represent the state sanctioned height of artistic merit and as such the data reveals how tradition and discrimination hide within the notion of artistic excellence and merit.”

In an important piece of research that exposes women’s under-representation across key sites of artistic recognition despite their sheer numbers, it is this statement that most strongly motivates my response – because I want to think about the power relations that it implies, and the ones that it obscures.

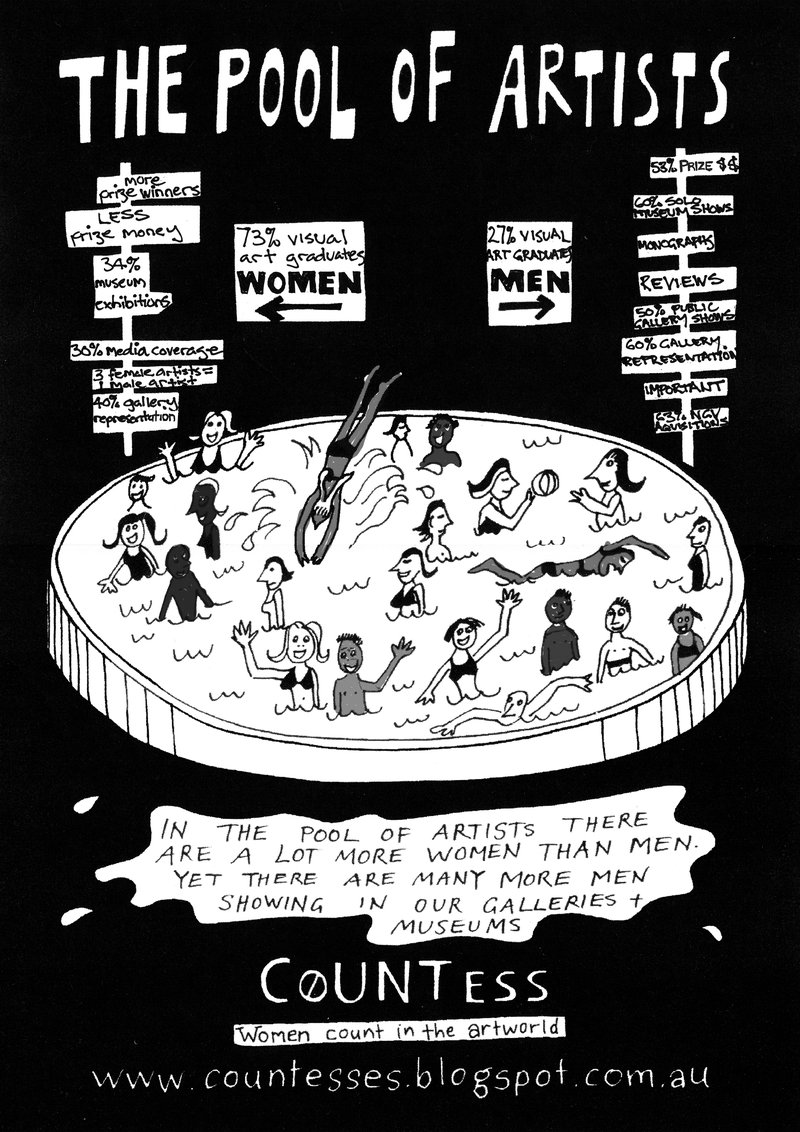

Elvis Richardson’s CoUNTess Blog has long been a reliable indicator of gender inequality in the visual arts – and, disappointingly, largely a lone voice. The typographic styling of “countess” is of course deliciously deliberate: she’s a lady counting cunts, and when she inevitably becomes irritating to those whose poor records she exposes, she becomes a bit of a cunt herself – and more power to her. Such regular research and reporting should not be left to what Elvis can get by trawling the publicly available data; there’s plenty more we ought to know and need to know so that we can get the full picture and take action. In this new CoUNTess Report, Elvis has enhanced the sophistication of the analysis, yet continues to draw only on “publicly available data collected from websites, exhibition catalogues, magazines and media.”

The reliance on public data doesn’t just limit the analysis to our having confidence in what’s reported. It also limits the analysis to the measures chosen by those institutions and by the bodies to which they report. And so we can readily learn about numbers and genders of artists exhibited, genders of key artistic staff, genders of artists whose work has won an award or been acquired by a gallery or museum.

But are those the best measures for understanding why the gender disparities still exist? There are so many steps between planning and presenting an exhibition, so many hurdles before being employed at a gallery or collected by a museum.

To understand gender disparity, I’d like to know: how many artist meetings are these institutions having each year? how many with female artists and how many with male? how many meetings are held with artists who are new to the institution? what kinds of relationships lead to such meetings? how far ahead are these institutions programming? and how does that correlate with gender balance? what proportion of invitations to exhibit are sent to female artists? how are they identified? is there a gender disparity in the numbers of artists who have portfolio websites with images and text easily accessible to curatorial and programming decision-makers? what prominence are (works by) male artists given in marketing materials, donor prospectuses, annual reports etc. compared with female artists? is there a sharp gender disparity among donors and patrons, as well as board members? on opening nights, what proportion of attending artists are female?

In brief, across every relevant context, who is making the decision to go with a male artist rather than a female artist? If it seems easier to the rushed decision-maker to choose a male artist, why is that? If it seems easier to the long-lead programmer to choose a male artist, why is that? On what basis are they making these decisions? Under what circumstances? And what would it take to shift that thinking?

Far too often, small and specific decisions that reinforce dominant power relations are made under banal circumstances. I do not imagine for a moment that there aren’t decision-makers with their own agendas, but in these difficult times, galleries large and small are highly motivated to do whatever it takes to differentiate themselves and attract numerous and loyal audiences, donors, patrons, sponsors and influential advocates. And feminism is getting hotter by the day.

For each expedience determined by a deadline-fuelled decision, for each action undertaken on the true or false assumption that that’s what the board or patrons or audiences would want, for each moment that inadvertent or blatant sexism isn’t called out, there is a breath to inhale, a conversation to reset, an ethics to unpack. And we are all responsible.

And so I return to that opening statement. Does the data reveal “how tradition and discrimination hide within the notion of artistic excellence and merit”? Or do “tradition and discrimination” belie the banalities of marketing schedules, donor development, acquisition drives, and all that non-artist-focused work which nonetheless tells an Australian cultural story? And how can we expose these moments? How might we count all of that instead?

State museums may represent a state-sanctioned view, but there is no state-sanctioned height of artistic merit. Only artists decide this. The relative success of the independent and artist-run galleries in addressing gender disparity is telling. If their processes are more elastic, if their networks are more responsive, if their conversations are more direct, then there’s plenty to be learnt by all institutions about artistic excellence and merit; and, of course, about how even the most banal decisions can power contemporary Australian feminism. Let’s CoUNT it up good.

Writer and curator Esther Anatolitis is Director of Regional Arts Victoria and a passionate advocate for the arts. estheranatolitis.net