Q&A with Djon Mundine

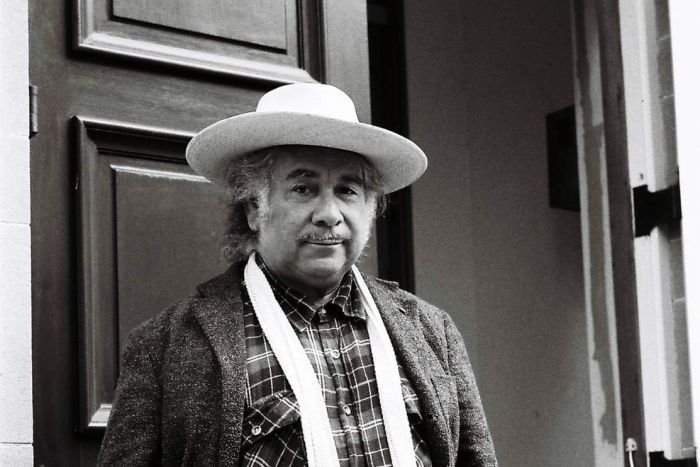

We interviewed curator, writer, artist and activist Djon Mundine.

We interviewed curator, writer, artist and activist Djon Mundine.

Image: courtesy Djon Mundine

TW: You describe yourself as an activist. How does this manifest in your curatorial practice?

DM: The activism comes from the fact historically there are very few Aboriginal artists curated into historical statements of their own. Very few people were curated as serious art. They were curated as curiosities or primitive artists so that’s what I worked against. As a curator you’re supposed to care, critique exhibitions, interpret, and to inform people about how the art was made.

With Australian Aboriginal art there is a particularly loaded colonial history so anything I did then became an active thing. As an activist I wanted to get Aboriginal art into the public domain and explain it as much as I could.

Although I lived in a so to speak traditional Aboriginal society, I did work with other people and tried to bring out the notion that there are many Aboriginal societies across Australia. It was as stupid to talk about them under the term ‘Aboriginal’ as it would be to talk about a Scottish person as an Englishman. People should realise the historical truth, that they all had different histories. There are commonalities but also marked differences.

TW: Would you say this is the main way you as an Aboriginal curator approached putting together exhibitions of Aboriginal work as different from the way a white fella curates?

DM: Maybe not so much, but historically we made a point of individualising the artists, to make evident that they existed as different personalities with individual styles and genres of art. Also part of bringing it into the domain of contemporary art was to bring it into the domain of contemporary economic return, so people weren’t being paid crap money for something that was very important, inventive and exciting. That’s what myself and other people worked collectively to make happen.

TW: For your ABC Awaye interview you talked through the last two decades of Aboriginal art and asked the question ‘Are we merely commodifying Aboriginality rather than living it?’ As a curator aren’t you being complicit in this commodification?

DM: In more recent years I’ve moved more towards people and the art world in general like it was in the 1970s. Every few years in Western art, people moved towards non physical art, to the ephemeral and things that are not so easily commodified. So I’ve moved more towards that as a practice.

I did initially try to structure exhibitions around particularly ideas so that people would see something; so the most ‘un-artworld’ person could come away and say I understand that now, I understand the use of colour, the association with place, and I understand how that particular image is read as the embodiment of somebody.

Things are now more spontaneously made; it’s more creation that you commodify rather than an object you can keep and lock up - film, moving image, performances - much in the same vein as people did in the 1970s in Australia.

TW: You’ve talked about what you aim to achieve through your approach to exhibition making and in terms of audience perception. What do you regard as a curatorial success and when would you know you had achieved what you set out to do?

DM: With the Bungarees Farm exhibition, I had artists sing who didn’t normally sing, I had people perform actions which they wouldn’t normally perform, and the choreography wouldn’t be what you would call dance. We were trying to get people to move outside their normal practice.

I had a couple of exhibitions which included artists of non-Aboriginal descent. With the 2014 TarraWarra Biennale exhibition Whisper in My Mask (curated by Natalie King and Djon Mundine) I talk about the idea of masking and the banality of White Australian society that constantly keeps masking itself. It’s moral guilt; a problem they won’t deal with, rather than making real moves to allay their guilt.

I don’t see it in terms of numbers; I don’t see it as blockbusters. It‘s more the response of your contemporaries, to see something in the artists’ works that they haven’t seen before. That might seem to be very rarefied or that I’m only playing to a certain audience but I want Western or Aboriginal artists in the (art world) game to come away and say they’ve never seen that in the artists’ work before.

Djon Mundine OAM is a member of the Bandjalung people of northern New South Wales with an extended career as a curator, activist and writer. His career has helped revolutionise the criticism and display of contemporary Aboriginal art. He was awarded an OAM in 1993.