Debates we don't need to have

NAVA asked several artists dealing both directly and indirectly with issues around queer identity and equality in their work to share their experiences of the Australian Marriage Survey.

NAVA asked several artists dealing both directly and indirectly with issues around queer identity and equality in their work to share their experiences of the Australian Marriage Survey.

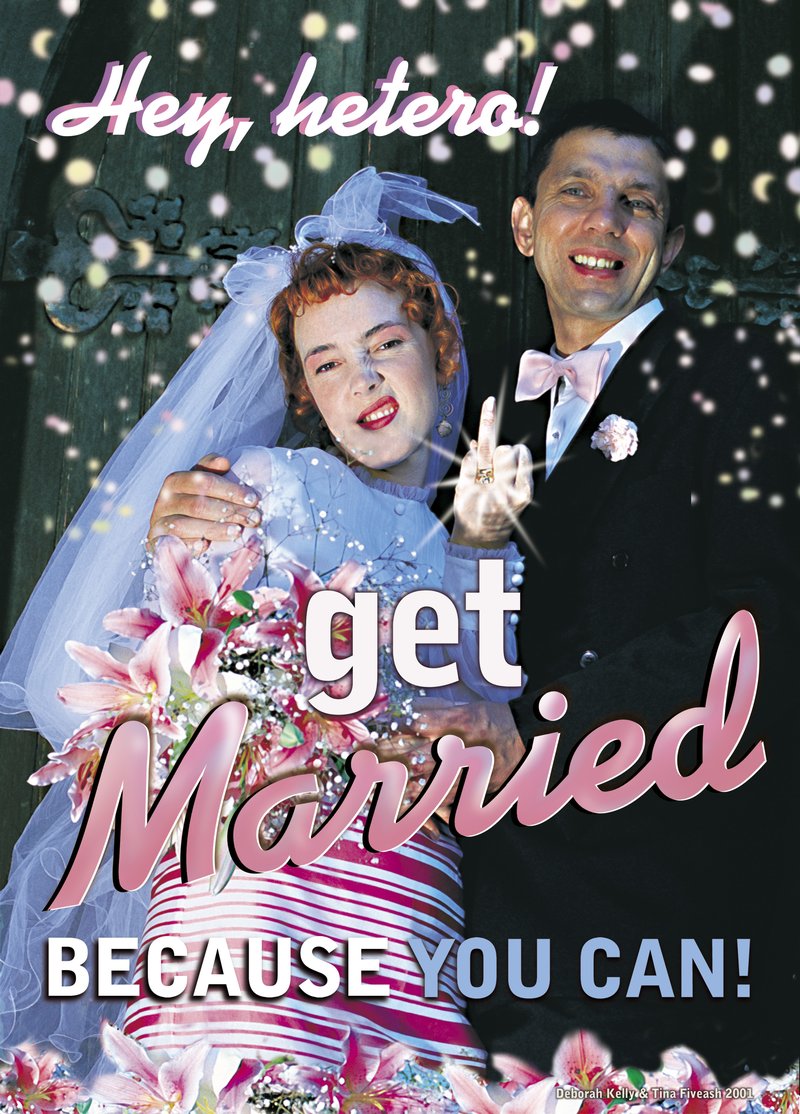

Image: Deborah Kelly & Tina Fiveash, Hey Hetero!, 2001.

“I feel it is important to accept that we all have similarities and differences in our perspectives of the world, sexuality and queerness is just one part of a perspective.”

The Australian marriage survey is having a greater emotional impact than many of us ever imagined. LGBTQIA people already enjoy most of the same rights and protections as other residents in Australia including equal age of consent, recognised de facto or domestic partnerships, access to IVF, joint and step-parent same-sex adoption (excluding NT), can serve in the military, and have the right to change their legal gender or register as 'non-specific' sex on federal legal documents. However, despite all of this, the public attitude to LGBTQIA people continues to be divided, and the Same Sex Marriage (SSM) survey has particularly sensationalised this division.

Across mainstream and social media, neighbourhood streets and skies, claims are being made that ultimately question LGBTQIA peoples very existence. Our families, relationships, identities and contributions have been erased by commentators and homophobia in the panicked pursuit of ‘saving’ institutionalised privilege. Marriage equality debates do not include the facts. They do not tell the diversity of our stories, our rights to equality before the law or recognise the many unions that we have already entered into.

This commentary is extremely hurtful and has created an environment filled with anxiety, anger, fear and exclusion. Beyond Blue, who recently reported a 40% increase in calls following the announcement of the postal vote say “LGBTQIA people experience higher rates of depression and anxiety, and are at greater risk of suicide, than the broader community. This is not due to their sexuality or gender identity, but because of the discrimination and prejudice they face.” [1]

This is not a fair state of existence. To ensure the experiences of the LGBTQIA community are heard, we invited twelve artists to discuss how their work contributes to positive queer visibility and how the same-sex marriage debate is impacting them.

Sāmoan artist Léuli Eshraghi rightly points out that “we have no right to legislate any kind of relationship until and only if First Nations governments wish to do so when treaties have been negotiated and majority of settlers recognise First Nations governments and cultural protocols.”

Léuli hopes his work contributes to understandings of non-heteronormative / non-homonormative ways of being and knowing. This is ever more important as he shares with NAVA that “the amplification of erroneous propaganda from the ‘No’ campaign has hurt my friends and myself in spouting gross mistruths about all sorts of relationships, visibilities and families. I think my practice has to serve as a counter to all the hateful vitriol, to be about care and hope.”

When asked about his work and position on the SSM survey, Ngarigo artist Peter Waples-Crowe reflects on the representation of Aboriginal people in popular culture and the struggle of being on the outside of two separate marginalised groups: Aboriginal and queer. His exhibition at Flinders Street Station earlier this year used the Dingo as a metaphor for second class natives - misunderstood, and seen as a threat to future. Peter declares “I want to be a proud queer elder. I want to be a voice for Indigenous queer people and artists. I’m sick of young people who are driven to suicide. I want to be a role model to young queer people. You can be Aboriginal and queer, these identities coexist and it’s ok.”

Deborah Kelly (pictured above) hopes that her work “addresses or reveals or indeed undermines the mechanisms of power, their scaffolding, their operations.” When asked about the SSM debate she says “right now the debate is making me so dismayed, so enraged, and so tearful, I don't know how to act as an artist, a citizen, a human being. This acute moment of being publicly judged by morons with megaphones so vividly suggests what it must ALWAYS be like to be Aboriginal, or Muslim, in this country.”

People on both sides of the argument are largely opposed to the non-compulsory, non-binding $122 million marriage survey and agree the issue should go straight to parliament. Former Coalition Prime Ministers John Howard and Tony Abbott recently criticised the Turnbull government saying they were "washing their hands of responsibility" to protect religious freedoms in the event of a majority Yes vote. [2]

Artist Owen Leong deals with identity, gender and repositioning the queer Asian-Australian body. “It is frustrating that the government has abdicated its responsibility to do the job it was elected to do, when the issue of marriage equality could have easily been resolved with a free conscience vote in parliament.” He continues “the current situation has wide-ranging negative impacts on the community, especially young LGBTQIA people who need our support and strength. As an artist, the current same-sex marriage debate certainly makes me take stock, refocus and consider how I can mobilise my artistic practice to become more politicised, engaged and to empower my community.”

Christine Dean’s work directly engages with queer culture and LGBTQIA history, over the past 5 years, she has been making trans specific work. “I see the same sex marriage debate as part of a continuum, the next step beyond the decriminalisation of male homosexuality, a historical event that I remember well. I was 20 at the time and dating my first boyfriend who I met at a youth group called young gays in 1983 and have been politically active ever since. Although my painting doesn't literally discuss marriage equality it aims to foreground issues relating to marginalised genders and sexualities.”

Nell, whose work embraces key themes of sex, rock ‘n’ roll, Buddhist philosophy, life, death and rebirth says “the world is a queer place. All my work is about finding peace and meaning between opposites.” On discussing the postal survey she says “I wake up every morning and think about the failure of democracy.”

The emotional toll of the SSM debate needs to be addressed. As queerness continues to be a target for hate speech, the failure of our society to understand how heteronormative privilege functions becomes evident. Basic human rights are not an entitlement to be voted on, but should be a given. It is the responsibility of the arts to provide the pathways for expression, empathy and action.

This month’s NAVA Artist File, Paul Yore explains “the very notion of queerness for me implies indeterminacy or a liminal space. So I am more concerned with moral ambiguity and ontological potentiality than I am in the fixed state of being generally implied by the limited view of personhood we have inherited in the West from the Judeo-Christian tradition. If that all sounds a little humourless, I should also state that I think a big part of radical queer politics is taking the piss, the use of acerbic wit and self-deprecation.” He says he is surprised to admit that he is feeling affected by the SSM debate but not in the way one might expect. “The limitedness of the same-sex marriage debate, I think, has sucked a lot of air out of arguably more important discussions, like addressing the high rate of queer youth suicide and homelessness and ending transphobia. I think the regulated and debased conversation around LGBTQIA+ issues demonstrates how culturally stagnant Australia has become - and we are again in a downwards spiral on all facets of national identity; it’s so disturbingly reminiscent of the Howard era.”

We at NAVA agree that the SSM debate is pivotal in the projection of equal rights in Australia. However, because of the mechanisms through which this discussion is happening, it has seen the issues relating to queer and non-normative representation and experience reduced to a single conversation. A conversation which fails to engage the whole difficult landscape that the community is endeavouring to traverse. It fails to acknowledge and celebrate differences.

Arone Meeks, a Kuku Midigi artist currently residing in Cairns, explores issues of identity and place in his work – specifically Aboriginal land rights and gay rights. He says “issues of Aboriginality, gender, ‘Country’ and sexuality have always been part of my dialogue. If we do not educate, speak up and be seen to have an active voice, then other people will make decisions/speak on our behalf.” In reference to the same-sex marriage debate he says “it boils down to who has the right to say no to people who want to love. Nobody. It makes me disappointed that the few seem to think they know what is right for the majority. Treating your fellow kind like misinformed fools, is unacceptable. Let people speak.” He continues “the Gender Spirit, that we all carry, that of Male and Female within, will always need nurturing and growth. To deny this within us, is to deny who we are. That’s everybody. Queer and straight.” Arone points out there are too many assumptions about people, he hopes what will come out of this is a better understanding that “difference is life”.

Artist and curator, Koulla Roussos, draws upon queer practices of scrutiny to call out unfairness and exploitation, she says she is “more influenced by Marx, Gramsci, Benjamin, Bourdieu et al, rather than specifically gender studies, using critical theory to examine the art industry as a cultural manifestation of an exploitative cultural hegemony, of which the SSM debate is one of many distracting phenomenons.” Also a barrister, who has practiced in the field of criminal law for over 20 years, Koulla says she has not seen any change in the rates of incarceration despite the human rights rhetoric she has been hearing and spouting since law school and beyond. “All I am witnessing is an increased rate of impoverishment, dysfunction, marginalisation which consequently is managed by the incarceration business model.” Like us and many of the artists we spoke to, Koulla notes the danger of aspiring to the limits of ‘equality’ or ‘sameness’. Perhaps embracing and celebrating difference is what we should be aspiring to. “I fear that the freedom that comes with being a deviant on the edge of society, critically exposing its exploitative practices has been lost since our ‘fluidity’ became contained by such governing instrumentalities as the ‘rule of law’ and its ‘institution of marriage’.”

Gary Carsley’s work speaks from the diversity of queerness to the pervasive conventionality of Australia. He explains that“queerness is not located in representations of the body or body parts as these are conventions projected upon queer cultural practices by straight society. In this era of facility, complexity is the new porn and given the collapse of memory - erudition and scholarship are the new obscene.” He continues “I think that images of resistance are now almost meaningless and that we have to look at developing practices that are themselves sites of resistance or opposition. Queer visibility is very quickly being commodified for consumption and we need to be mindful that queer needs to push back against becoming some sort of emollient for the abrasiveness of capital.”

The thing is, regardless of whether you believe in marriage or prefer to sit of the side of difference and subscribe to FSU (fck sht up), under the law, marriage gives people access to a complete package of rights that are recognised nationally and internationally. What marriage means on a commodified level, is not something everyone is interested in, however in sickness or death, marriage under the law means an entirely different thing. Being protected and recognised under the law is important, especially when parents and families continue to reject same-sex relatives and couples. This is why it’s worth fighting for.

Vietnamese-Australian artist James Nguyen explores the complexes of familial relationships in his work and tells me “the struggle for equality, justice and compassion are good things to consider when making art.” He says the SSM debate is having a definite impact on the way he thinks about his practice “the courage and graciousness that people have demonstrated when facing really toxic and cruel provocations have galvanised my love for the community and strengthened my resolve to support and speak up in whatever way I can.” He continues “on an individual level, I don’t feel that I have the capacity to make a huge contribution to LGBTQIA visibility. However, the cumulative generosity and growing visibility of more articulate LGBTQIA artists working around me generates a powerful space for people like me to feel I can participate and add to the conversation. As these voices coalesce, so does the momentum towards change. Not only is there strength and safety in numbers, but also much optimism and inspiration.”

So, let’s encourage widespread fairness and equality, let’s ensure the yes vote succeeds and that this happens by recognising our differences, our agency and our rights.

Penelope Benton and Brianna Munting, Acting Co-Executive Directors, NAVA

Marriage survey voting packs have been sent out across the country. If you haven’t voted and posted it back already, we encourage you to do so now.

If you haven’t yet received your survey, you can request a new survey be sent to you, similarly if you have moved house but not updated your address, you can still do so through the ABS website www.marriagesurvey.abs.gov.au or by calling the Information Line on 1800 572 113 and a replacement form will be sent to you.

The ABS encourages ballots to be returned by 27 October with a final deadline of 7 November.