A handy guide to reading government budget documents

NAVA has asked me to write a handy guide to reading government budget documents. So, here goes.

NAVA has asked me to write a handy guide to reading government budget documents. So, here goes.

Graphic: Title page of the Portfolio Budget Statement for the Department

Budgets are important documents. Because money talks, they are the master policy documents for any government. The old saying is that “a budget is a political document”. That’s true, but if you learn how to read them, you can cut through the spin and work out exactly where the government is spending its money. Which is your money, in the end.

How do I know how to do this? I’ve spent years as a policy journalist.

Every year for a decade now, I’ve gone to Canberra for the famous “lock up”, where they literally lock you in a room in Parliament House, and let you read the budget before it is released to the public at large.

The idea of budget lockups is that, by forcing the journos to actually read the thing before they report on it, it leads to better journalism, or at least better-informed journalism.

I’m not sure that’s true, but there’s no doubt that quality journalists get a lot out of the process. I’ve sat next to Michelle Grattan in previous years. It’s quite something to listen to a 40-year veteran dictate her analysis at what feels like the top of her voice, while you’re racing to write your own article.

Budgets are enormous beasts. They generally have four volumes and a bunch of ancillary files, and they run to multiple megabytes and thousands of pages. The federal budget comes in several sections. Budget Paper 1 is the hard-edged economic analysis, and is mostly written by the boffins at Treasury. Budget Paper 2 is probably the most useful document: it contains all the actual spending and revenue decisions, and what their impact will be for the budget bottom line. If the government is raising a tax, or cutting spending to health or education, it will be listed in Budget Paper 2.

What you look for in a budget depends on what information you’re seeking.

Economists and economic journalists look at the economics section, and the all-important Treasury forecasts. These generally turn out to be wrong, but they are vital because they tell you what the Treasury thinks will happen to the economy. Is there a resources boom? A recession? A period of stagnant wages? Budget Paper 1 tells you.

Political journalists look for the political narrative woven through the numbers. They’re interested in how the government in the big picture spending and revenue decisions the government has made, and how they might affect the electorate. The Treasurer gives a speech, which is of course full of spin and political tactics. They will quote form this and then decide if the numbers reflect that rhetoric.

Journalists interested in a specific policy area will generally navigate straight to that section of the budget.

For those interested in cultural policy, the most important bit is the so-called Portfolio Budget Statement. Every ministry and department must compile one of these. It is the master budget for the entire Department for the next financial year. The Department of Communications and the Arts publishes one every year, containing the budgets for that department and all the agencies that sit inside it, including the ABC, Screen Australia, the national galleries, archives and museums, and the Australia Council.

For someone interested in cultural policy, the PBS for Communications and the Arts is well worth a read. It sets out in reasonably plain English exactly what the government thinks this department does. For instance, last year it told us that “the Department of Communications and the Arts aims to promote innovative communications and cultural sectors through policy, program and service delivery to the benefit of all Australians.”

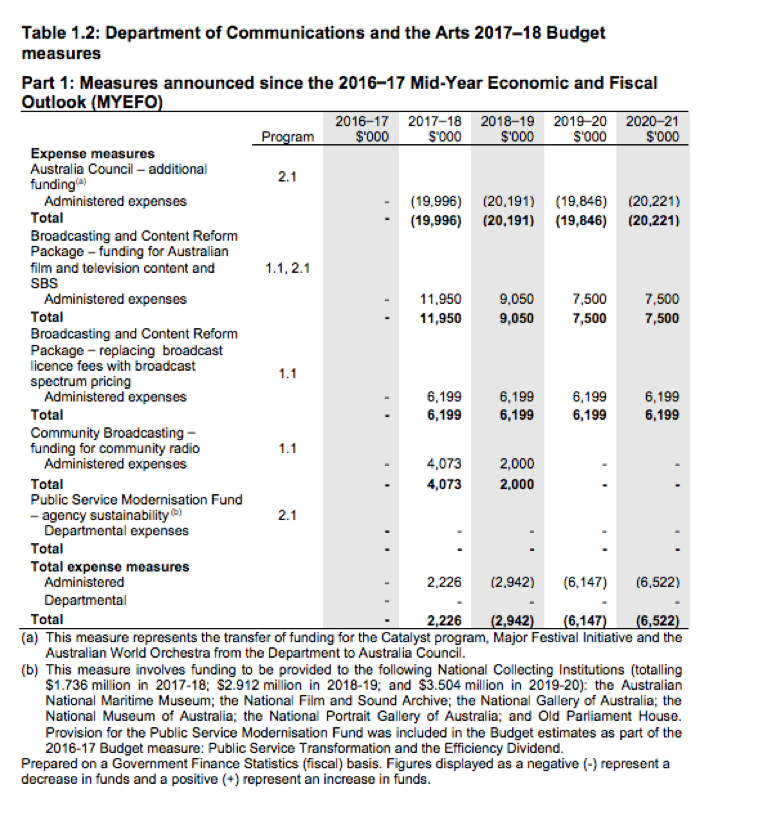

In terms of the budget, the most important tables are the ones dealing with budget measures, and the ones called “budgeted expenses.” Budget measures tell you about decisions made since the last economic statement. Here’s an example from last year:

A few quick points: all figures are in thousands. A figure of 11,950 means $11,950,000 or $11.95 million. Figures in brackets are subtractions. These can be tricky. Sometimes a figure can be a negative subtraction – in other words, an addition. The figure of (19,996) in the 2017-18 column in the table above is a subtraction of approximately $20 million from the Department in that year, but the money is going to the Australia Council, so it’s actually a funding boost for OzCo. You will only work this out by reading note (a) at the bottom of the table … always read the fine print! A third important point is that the budget projects forward four years: the coming financial year and the three after that. This four-year period is called the “forward estimates”. Decisions can therefore be baked in for coming years from decisions made in previous budgets.

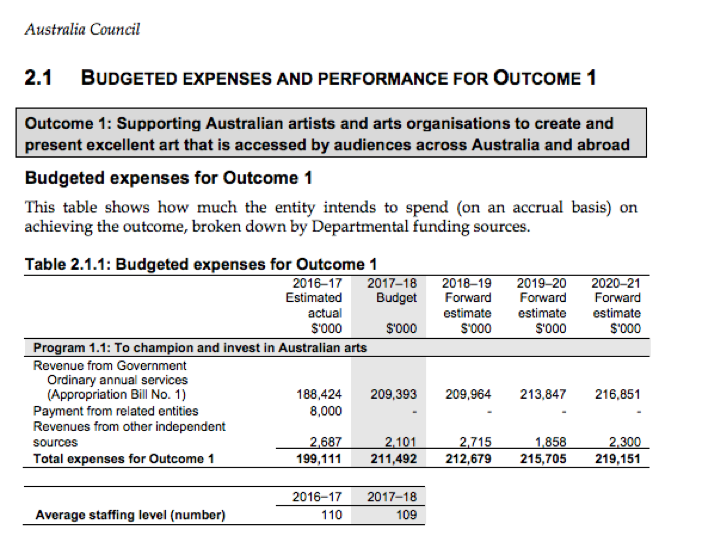

This is what a budgeted expenses table looks like, this time for the Australia Council.

Table 2.1.1 here shows you what the Australia Council’s “estimated actual” funding was in the about-to-finish financial year of 2016-17 (remember, the budget was handed down in May 2017).

That figure is $199.1 million, of which $188.4 million was normal government funding (the so called “ordinary annual services”). The 2017 budget says the Australia Council will get increased funding in the coming year, of $209.4 million (remember that $20 million coming from the Department?), and it will make some revenue of its own of $2.1 million. So, its overall budget is $211.5 million, rising slowly to $219.2 million in the 2020-21 forward estimate. There is also a figure for average staffing, of 109 full-time equivalent staff members.

Of course, budgets can change at any time. The government went on to cut funding to the Australia Council in the 2017 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, which means the 2018 budget will show the Australia Council with an estimated actual of something less than $211 million. Politics is a risky business, and budgets can be cut throughout the year by panicky ministers and governments.

Another important factor is inflation. The Australia Council will get a small numerical increase from 2017-18 to 2020-21 (the economists call a figure that doesn’t adjust for inflation “nominal”) of 3.8 per cent. But that’s 3.8 per cent across three years. If inflation runs at 2.5 per cent a year, the Australia Council needs a budget increase of 7.5 per cent across three years or it will go backwards in real terms. So that figure of $219 million in 2020 is actually a budget cut in real terms. This is what austerity looks like.

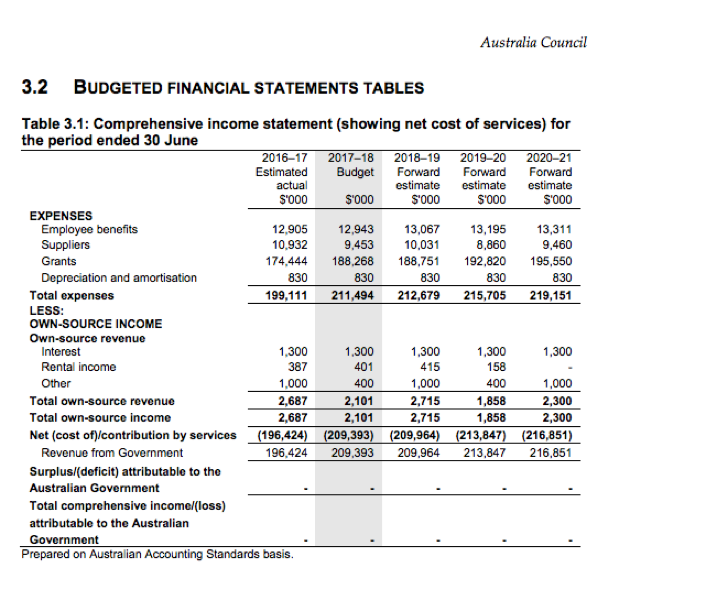

Do we want a breakdown of expenditure? The budget gives us that too, at least at the top level.

Of that $211.5 million the Australia Council expects to spend, employees make up $13 million, suppliers (mainly rent and operating expenses) makes up $9.5 million, and grants account for $188.3 million. The Australia Council is a very lean organisation: 89 per cent of its expenditure goes to funding art and culture. You can also delve into the agency’s cashflows and assets, but these are generally less interesting.

Want more information than this? You’ll have to go to the Australia Council’s annual report, and perhaps even delve in Senate Estimates, where members of the upper house can ask questions of Arts Minister Mitch Fifield and Australia Council CEO Tony Grybowski, and get them to explain certain figures and decisions.

Once you’ve read a few budgets, you will learn how to read them more quickly. If you follow the budget of a Department or an agency for a few years, you start to get an idea of whether times are good, or tight, and where the money is coming from, and going to. As the joke goes, remember the Golden Rule: he who has the gold makes the rules.

Dr Ben Eltham is a lecturer in the School of Media, Film and Journalism at Monash University. He also writes regularly about Australian politics and culture for the popular media. His recent book on Australian arts policy in the Brandis years, When the Goal Posts Move, was published in 2016 by Currency House.