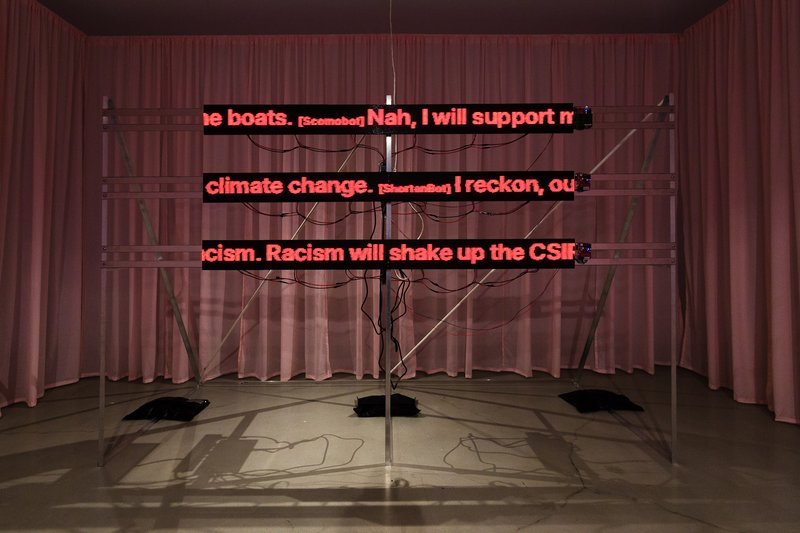

In the post-truth ‘fake news’ era, the work of researchers and academics turns far too frequently to the inaccurate and misleading statements issued by politicians.

Given the complexity of the arts and cultural sector, a little confusion is understandable. All through the COVID19 crisis, however, the industry has devoted considerable above-and-beyond time to providing detailed statistics, analyses and case studies, outlining what’s at stake in the absence of a comprehensive national focus. This information has also been released publicly on a regular basis, giving audiences and stakeholders the confidence that we’re redressing the health, economic and cultural aspects of this emergency.

The contributions of the Australian Government to these public discussions have required a great deal of scrutiny. Let’s fact-check some recent claims.

What is the value of COVID19 income support to the arts and culture industry?

- Claim: JobKeeper “will end up being worth between $4bn and $10bn of support to the creative workforce, making it the single biggest government investment to support our arts and creative sector that we have ever seen.” (Paul Fletcher, The Guardian 23 April)

- Claim: “Our other measures are also flowing into the arts sector – such as cashflow support, which has been worth more than $23m to the businesses in the creative and performing arts group to date.” (Paul Fletcher, The Australian 9 June)

- Claim: “We’ve spent seventy-six billion dollars already on JobKeeper and the arts... and it’s been comparatively successful” (Senator Andrew Bragg, Q and A 47’47” 8 June)

- Claim: “There is no basis for the urban myth that somehow the arts sector has been dudded by JobKeeper.” (Paul Fletcher, The Australian 9 June)

- In fact, JobKeeper, cashflow support and all other measures exclude local government, Australia’s biggest owners of galleries, museums and performing arts centres, a massive arts employer

- In fact, JobKeeper, cashflow support and all other measures exclude universities, who are substantial owners of internationally renowned museums, galleries and collections, as well as housing Australia’s leading art schools, and are also a leading employer of artists and arts experts

- In fact, JobKeeper excludes casuals who’ve been with their employer <12mo, which is the common practice across all artforms for artists and artsworkers

- This claim has also been contradicted by the Government’s own statement: JobKeeper made “total payments of $76.1m” in April to “creative and performing arts” workers (Paul Fletcher, The Australian 9 June)

- The claim is also challenged by the $60bn JobKeeper underspend, which calls all government projections into question.

How has a casual workforce disadvantaged the arts sector from access to income support?

- Claim: “Nor is it true that the arts sector is uniquely disadvantaged because of heavy use of casual employees. Only 3 per cent of casual workers are from the arts and recreation services sector, compared with 20 per cent from accommodation and food services and 15 per cent from retail.” (Paul Fletcher, The Australian 9 June)

- In fact, it’s the proportion of casual workers within an industry sector, and not across the entire workforce’s casual labour, that might uniquely disadvantage that industry in relation to the entire workforce

- In fact, in the visual arts, 42% of workers in the small-to-medium sector are casual (Rod Campbell, Cameron Murray, Sam Brennan, Jordie Pettit, S2M: The economics of Australia’s small-to-medium visual arts sector, 2017)

- In fact, of practising professional artists across all artforms, 30% are employed casually for their arts-related work, and 35% are employed casually for their non-arts-related work (David Throsby and Katya Petetskaya, Making Art Work: An economic study of professional artists in Australia, 2017)

- In fact, 23.4% of arts and media professionals are employed on a casual basis, and 33.9% of casuals in arts and recreation services had been with their employer less than a year (Australian Bureau of Statistics, COVID-19: Impacts on casual workers in Australia, a statistical snapshot, 8 May).

The industry has been united and clear in identifying priorities and gaps – in an open letter to the Prime Minister in March, in a response to one of Minister Fletcher’s opinion pieces in the Guardian in April, and again this week in several statements bringing thousands of artists and artsworkers together.

What is the size and scope of the arts and cultural industry?

- Claim: “The Bureau of Communications and Arts Research (BCAR) has released new analysis showing cultural and creative activity contributed $111.7 billion to Australia’s economy in 2016-17.” (Bureau of Economics and Arts Research, October 2018)

- In fact, the full size and scope of Australia’s arts and cultural industry is not known. This is partly because of definitional issues: as we’ve seen above, the ABS looks interchangeably at “arts and recreation” or “arts and media services”, for example. As John Daley, CEO of the Grattan Institute, put it in a recent NAVA Advocacy Program interview: if we were to add up all the estimates of the scale of each sector of the economy, they would “add up to an awful lot more than the totality of the Australian economy.”

- In fact, the BCAR’s $111.7bn figure omits significant elements of the visual arts economy including the creation, exhibition and sale of contemporary art in public and commercial galleries, the secondary market of sales at auctions or through dealers, and the work of all Aboriginal Art Centres. The economic contribution of Australia’s painters, sculptors, photographers, public artists and so many other contemporary practices has not been considered at all. So while $111.7bn or 6.4% of GDP sounds like a great big contribution, it’s actually an underestimate. More work is needed here.

Questions for researchers, journalists and policy-makers to put to the Australian Government:

- Why the selective and oblique choice of easily refutable data?

- Why have income support measures not been made available to universities and local government? Why have they not aligned with the needs of one of Australia’s worst-hit industries?

- How has the pandemic improved your understanding of how the arts and cultural industry functions, how its people are employed, and how its industry interdependencies power consumer confidence and economic recovery?