Fletcher’s “significant re-imagining of the Commonwealth’s approach to the arts” falls short

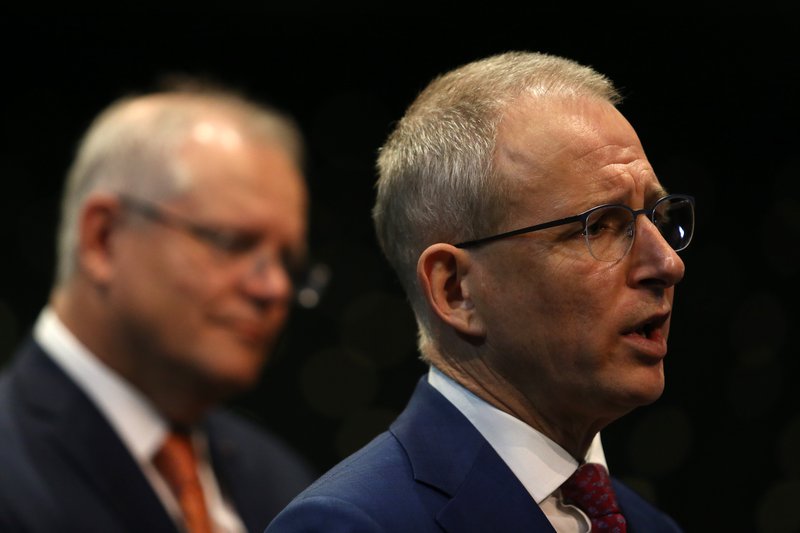

Image: Minister for the Arts Paul Fletcher, (background) Prime Minister Scott Morrison. Photo by Matt Blyth/Getty.

Image: Minister for the Arts Paul Fletcher, (background) Prime Minister Scott Morrison. Photo by Matt Blyth/Getty.

Earlier in April 2021, Minister for the Arts Paul Fletcher gave a speech at Sydney Institute where he noted that the value and importance of the arts sector to the Australian identity, economy and people cannot be underestimated. Expressing his commitment and support for the industry, he reminded listeners of the arts recovery package and past contributions by the Coalition to the arts.

Conveniently, Fletcher failed to acknowledge the steady decline in available arts funding relative to population growth over the last decade (expenditure in the cultural area fell 18.9% per capita between 2008 and 2018). Nor did the Minister mention the Coalition’s decision to facilitate the disappearance of the federal arts department by merging it into the new Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications.

Never mind his Government's choice to ignore the united calls from the arts sector for urgent, comprehensive stimulus during the pandemic. Responding to Fletcher’s claim the “level of funding committed to the arts by the Morrison Government in 2020-21 has been unprecedented”, Associate Professor/Principal Fellow (Hon) at the University of Melbourne, Jo Caust, reminds us in The Conversation:

Belated additional funding for COVID relief may have increased the federal arts allocation dramatically for the past 12 months. But this additional funding has not been equitably allocated, and the government has continued to ignore cultural workers who were not eligible for JobKeeper or JobSeeker.

With the dramatic contraction of the Australia Council's discretionary funding, which had been used to support the core operations of small-to-medium organisations and independent artists, the engine room of contemporary artistic practice is in real danger. It is here that the cultural work is generated which will become the expression of Australia's cultural identity in the future.

When considered alongside similar trends in state government arts budgeting over the past years, a bleak forecast is painted for the sustainability of our major cultural institutions, small-to-medium arts organisations, as well as the specialist staff they employ and the Australian artists they present.

In between multimillion-dollar funding cuts flagged for NSW’s major cultural institutions, the NT Government’s 11% cut to the Museum and Art Gallery of the NT (MAGNT) budget, and a 10% staff reduction at Victoria’s National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in 2020, the quality of Australia’s art and programming is at risk.

These operational budget cuts are compounded by the annual efficiency dividends that apply every year to all government departments in order to generate budget savings. Introduced by the Hawke Government in the late 80s, this annual funding reduction (varying between 1% - 2.5%) was rationalised on the expectation that small efficiency improvements will generate savings. Efficiency dividends are similarly applied to the operations of most state and territory governments.

The cumulative effect of year-on-year cuts to operating budgets, which are especially felt by arts workers, are devastating. The size of the operating budget determines what can be planned outside of the basic upkeep of the state’s institutions – basics like administrative staff, rent and office expenses, marketing and audience development, all of which tend to increase each year with general inflation. While project funding allows organisations to create and present work and pay artists fairly, that kind of funding does not support core operations – administrative costs are explicitly excluded.

Undermining the solid core of operational sustainability strips the capacity of our cultural institutions to deliver rich, diverse and innovative exhibitions that drive domestic tourism and economic growth. Furthermore, this curtails their ability to absorb economic shocks such as the pandemic recession.

The fatigue felt by many small-to-medium organisations is exacerbated by the unsuitability of the federal government’s Restart Investment to Sustain and Expand (RISE) Fund criteria, which is intended to “assist the presentation of new or re-shaped cultural and creative activities and events”.

The eligibility requirements excluded Commonwealth, State or Territory government agencies or bodies (including government business enterprises), which means that many university and local government run galleries, who do not have an ABN distinct from the Council, were excluded. Under the changes to the guidelines yet to be released, local government owned organisations will now be able to apply for RISE.

Many of the remaining organisations that are eligible for the fund, are so preoccupied with the recovery of core organisational funding, that they have very little resources to expand or develop new projects.

The RISE Fund falls into the “one-size-fits-all” approach to arts public funding where once again the government has failed to acknowledge that different parts of the arts ecosystem are financed in different ways. According to the National Association for the Visual Arts’s (NAVA) 2017 report The economics of small-to-medium visual arts sector:

Simply allocating money to a new government program is not an effective means of funding the arts. Governments must understand which parts of the arts ecosystem they are funding and why, what challenges those organisations are facing, and what the implications of those challenges are for other parts of the ecosystem.

The belated arts support package currently offered suggests there is some truth to Fletcher’s recognition that culture is valued by the government. Yet the narrow focus on entertainment and events does little to encourage stable sector recovery from the impacts of successive years of funding cuts and the recent bushfires, floods, storms, Covid-19 shutdown and economic recession.

Published in The Conversation, Julian Meyrick, Julianne Schultz and Justin O'Connor argued that, ‘Where the policy debate has focused on a need to 'rescue' the cultural sector from the ill-effects of COVID-19, the emphasis must now be on growing it as part of a wider program of public investment.’

There has never been a better time for the Coalition Government to implement a national arts and culture plan with a set of strategies for stimulating Australia’s creative output and Australian culture through increased funding and programs across the three-tiers of government. Generous investment is required to nourish a sustainable model that can guarantee state, federal and international cultural programs and visitation.

Active leadership requires listening to local expertise and grassroots knowledge, and industry representatives who can provide culture-specific expertise and a comprehensive understanding of the full scale and scope of all parts of the arts ecology. The Creative Australia policy, drafted and released in 2013 prior to the change in government, sets out five overarching goals, developed in close consultation with the community and provides an ambitious framework to build on.

Covid-19 has given us a chance to reimagine arts policy, and a useful starting point is recognising the critical role art and culture plays in a post-Covid recovery through a broader policy agenda and committing sustained funding needed to see it through.